Cut-Paw-Paw Sanatorium

Every infectious disease that would afflict Melbourne’s early European settlers was imported, with the new arrivals creating the necessary ecologies for these old-world diseases to flourish in their new environment. Measles was first brought to Victoria (and Australia) by the ship Persian in 1850, but it did not assume epidemic proportions until 1853-54. From then until 1900, measles came in sharp epidemics with high death rates between 50 and 200 per 100,000; the worst outbreak being in 1874-75. Measles’ notorious debilitating effects on the immune system prepared the ground for Victoria’s worst epidemic of scarlet fever in 1875-76 and for a rise in tuberculosis deaths over the next decade.

and for a rise in tuberculosis deaths over the next decade.

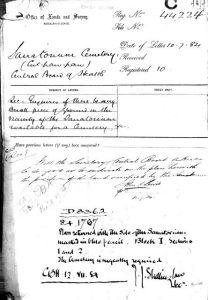

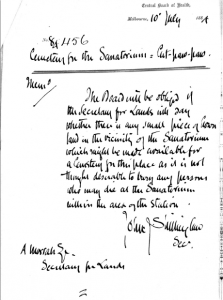

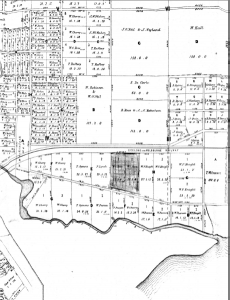

By 1882 the government of the day decided to establish a sanatorium somewhere on the outskirts of Melbourne. After much discussion as to the most suitable site for such an establishment, the government made available almost 50 acres of land about 1 and 3/4 mile west of the North Williamstown Railway Station. The site was sufficiendy isolated yet, being on the outskirts of Williamstown, it was reasonably close to the main port of entry to shipping at the time. In the year of 1884 a virulent outbreak of small-pox occurred within Melbourne and a decision was made to establish a cemetery and quarantine on the northern border of Williamstown.

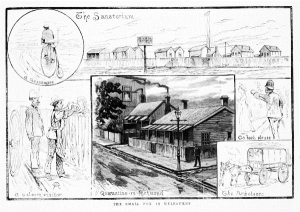

The Sanatorium was described, in a report appearing in the Williamstown Chronicle 1894, as follows:

The Sanatorium was described, in a report appearing in the Williamstown Chronicle 1894, as follows:

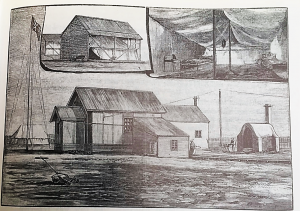

“The huts which serve as wards are altogether unsuitable for persons suffering from any form of disease, being exceedingly draughty; not admitting of being maintained at even a tolerably uniform temperature, and being exposed continuously to foul and, in wet weather, to damp soil air from beneath the flooring hoards. Moreover, there is no proper arrangement for bathing or for cooking. In fact, the conditions at this establishment are unfavorable to recovery. Want of proper bathing arrangements necessitates a prolongation of quarantine in almost every case, more particularly in the case of females, beyond the period which would otherwise be required. The want of a properly drained exercising ground for the convalescents has a markedly depressing influence upon them. And the insufficiency of the fencing round the establishment, as also the unsatisfactory conditions under which the caretaker has hitherto been allowed to continue in the cottage, provide means whereby infection may at any time be transmitted from the buildings, which, as already stated, it is impossible to render uninfective [sic]. On the north, west, and south the Sanatorium was bounded by an old creek choked with rotting vegetation, while on the east side a filthy, fever-reeking swamp encroached and added to its dismalness.”

In a report from the Central Board of Health (1885), details of the Sanatorium and its buildings: ‘situated between the Geelong and Ballarat Railway and the road from Williamstown to the Racecourse, about 1 & 3/4 miles from the North Williamstown Railway Station. In the portion of the paddock nearest to the railway fence an area of 1 & 1/2 acres was close fenced with 6 feet high palings to secure isolation for the necessary tents and other buildings. At about 2 chains of marginal distance from the fencing, strips of land 1 chain wide were ploughed and some trees planted to afford shelter against the cold and strong winds which so often prevail across this flat, open country.’ (Williamstown Historical Society newsletter No. 88, 1985, p. 5). The buildings themselves were described as being tents that were floored and had wooden framework and corrugated iron roofs.

With no public housing of any note for two miles in any direction, the buildings, which were surrounded by a 6 feet high paling fence, were rarely seen by Williamstown residents and for most their existence remained a mystery. The high fence surrounding the enclosure prevented patients escaping and kept inquisitive members of the public from venturing onto the land. To guard against the likelihood of a grass fire destroying the facility the authorities took the precaution to plough an area of land approximately 30 feet in width, and some 60 feet from the surrounding fence. Within those confines a number of trees were then planted to act as a wind break.

The Sanatorium was under the direct control of the Central Board of Health and managed by Messrs R. Grimwood, Shillinglaw, Murray and one other. Little is known of these men other than that Mr Murray appeared to be an old sailor and responsible for the construction and rigging of the flagpole. Warne’s cab was used as the means of conveyance to and from the sanatorium. By 1885, such was the demand that other than the accommodation for patients, there was aslo a residence for the doctor, another for the caretaker, a stable and shelter shed for the ambulance driver and his horse. Persons who had died, from an infectious disease elsewhere, would be transported to the

The Sanatorium was under the direct control of the Central Board of Health and managed by Messrs R. Grimwood, Shillinglaw, Murray and one other. Little is known of these men other than that Mr Murray appeared to be an old sailor and responsible for the construction and rigging of the flagpole. Warne’s cab was used as the means of conveyance to and from the sanatorium. By 1885, such was the demand that other than the accommodation for patients, there was aslo a residence for the doctor, another for the caretaker, a stable and shelter shed for the ambulance driver and his horse. Persons who had died, from an infectious disease elsewhere, would be transported to the  Sanatorium in a special pitch-covered coffin and then cremated. It was also reported (Williamstown Chronicle, 1929) that a number of Lascars from the mail-boats, who died at Williamstown, were also cremated there.

Sanatorium in a special pitch-covered coffin and then cremated. It was also reported (Williamstown Chronicle, 1929) that a number of Lascars from the mail-boats, who died at Williamstown, were also cremated there.

(Lascar seamen were assigned servants, mainly from the Malibar coast of India, who were renowned for their seamanship. They were contracted to work on the large British and European shipping lines from around the fifteenth century up until the Second World War. The Lascars worked as deck hands and cooks, as well as in menial roles. Lascars were predominately Muslim.)

A report in the Williamstown Chronicle, March 1897, noted that “The Cut-Paw-Paw Sanatorium is condemned by the Board of Health (Dr Greswell, the Victorian Government’s Chief Medical Officer) as unsuited for the purpose of its original construction. This will cause no surprise locally, for at the last Williamstown Council meeting the collection of dilapidated looking structures were unhesitatingly pronounced unfit to send a sick man into, without it was with a sinister desire to terminate his earthly career.” Additionally, the article noted that the accommodation was  only adequate to meet the requirements of a limited outbreak at best. It would appear, however, that the Sanatorium and /or its cemetery did not close entirely because in 1900 Robert Sheppard Alway, the Camberwell bubonic plague patient, succumbed to that disease at 7 o’clock last Thursday evening, and, in accordance with the dictates of Dr Gresswell, chairman of the Board of Public Health, the body was at once conveyed to the Cut-Paw-Paw sanatorium, Williamstown, in a special pitch-covered coffin, and just after midnight cremated on a huge wood pyre (Williamstown Chronicle).

only adequate to meet the requirements of a limited outbreak at best. It would appear, however, that the Sanatorium and /or its cemetery did not close entirely because in 1900 Robert Sheppard Alway, the Camberwell bubonic plague patient, succumbed to that disease at 7 o’clock last Thursday evening, and, in accordance with the dictates of Dr Gresswell, chairman of the Board of Public Health, the body was at once conveyed to the Cut-Paw-Paw sanatorium, Williamstown, in a special pitch-covered coffin, and just after midnight cremated on a huge wood pyre (Williamstown Chronicle).

Happily there were few deaths recorded at the sanatorium and after the epidemic of 1883-85 the smallpox threat retreated. For instance, between 1898 and 1904 only three cases of smallpox were reported in Melbourne. Of these, two were quarantined at their own homes and only one – a recent immigrant – was sent to the Cut-Paw-Paw Sanatorium. The institution also had one smallpox victim transferred from quarantine at Point Nepean in 1899.

The graves at Cut-Paw-Paw were left to themselves. So rapidly does time impose its will that within a few years all obvious traces of the sanatorium, including the graveyard, had disappeared.

There was little recorded about the Sanatorium after this date until an article appeared in the Williamstown Chronicle in 1929 – Old Graves Discovered at West Newport. The article notes that: “While clearing, boxthorn hedges and noxious Weeds from the vicinity of the Geelong railway line, near the freezing works this week, the workmen came across several mounds, which, on closer examination, were found to be graves. Some of the graves had headstones. It will be remembered by early residents that forty years ago a sanatorium was located at this spot, just between Kororoit Creek-road and the railway, where it runs off for Altona from the main line.” Headstones that were identified included John Barker (1884), C J V Wilmot (1884), John W Humble (1884), and Captain Anderson (1884). All appearing to be victims of the small-pox outbreak of that same year. Another person by the name of Harry Searle (1884) also died from small-pox at the Sanatorium but due to his celebrity status was buried elsewhere.

graves. Some of the graves had headstones. It will be remembered by early residents that forty years ago a sanatorium was located at this spot, just between Kororoit Creek-road and the railway, where it runs off for Altona from the main line.” Headstones that were identified included John Barker (1884), C J V Wilmot (1884), John W Humble (1884), and Captain Anderson (1884). All appearing to be victims of the small-pox outbreak of that same year. Another person by the name of Harry Searle (1884) also died from small-pox at the Sanatorium but due to his celebrity status was buried elsewhere.

Harry Searle was stricken with small-pox on his return from England where he had won the world’s sculling championship on the River Thames. Searle was twenty-three at the time. He was regarded as a superb athlete and the newspapers detailed that he was 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighed 11st 6lb in full training, and that his daily training since schoolboy days involved rowing six miles a day – which (as the Town and Country Journal expressed it) ‘for a mere boy must necessarily have hardened both muscles and constitution.’ Born in Grafton, NSW, he was soon winning sculling races in Sydney. Rowing had a much larger public following than today and his match against the Canadian champion William O’Connor on the Thames in September 1889 attracted a big local crowd, a considerable amount of betting and great interest in Australia.

Soon after his triumph, Searle was on his way home aboard the Austral. After the ship had called in at Colombo, Searle developed symptoms of typhoid. His condition was soon critical, and he was offloaded as soon as the ship reached Melbourne. He was sent at once to the sanatorium, arriving on 22 November. He died on 9 December of that year.

Searle was not buried at the sanatorium cemetery. He asked for a quiet burial, but was given the reverse. This is curious, since others who died at the sanatorium were consigned to burial in the bleak ground of Cut-Paw-Paw. But Searle’s death was a matter of great public grief and the funeral procession was exceptional. Perhaps in a gesture towards securing the public health, his body was placed in a leaden shell before being taken to the mortuary of AA Sleight in Richmond. There the shell was encased in a coffin of polished oak bearing a silver shield. A procession from Richmond to Spencer Street Railway Station was headed by representatives of rowing, cricket, football and athletic associations. From here the body was taken by express train to Sydney where, according to press reports, flags were flown at half-mast, shops were draped in black and ‘the late champion’s colours with accompanying crepe are worn by many in the street.’ When it arrived in Sydney, the train was mobbed.

Finally, a memorial service was held in St Andrew’s Cathedral, where members of parliament and the mayor of Sydney were the pallbearers. From here the coffin was conveyed to Circular Quay and transferred to a coastal steamer, which took Searle back to his hometown on the Clarence River. Here he was buried, and later his admirers erected a memorial near Gladesville on the Parramatta River in Sydney. It was in dramatic contrast to the burial of, and memorials to, the other people who died at the Cut-Paw-Paw Sanatorium.

References:

Elsum, W.H., The History of Williamstown, 1985, Williamstown City Council, Victoria

Strahan, L., At the Edge of the Centre: A History of Williamstown, 1994, Hargreen Publishing, North Melbourne, Victoria

Illustrated Australian News, 3 September 1884, page 133

Williamstown Chronicle, 16 August 1884, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 22 January 1886, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 2 June 1894, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 27 March 1897, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 9 June 1900, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 19 January 1929, page 2

Williamstown Chronicle, 26 January 1929, page 2

Photos: State Library of Victoria collection (Accessed 2019)

Sketches: Illustrated Australian News and State Library of Victoria

Map and Land Office Documents: PROV record VPRS 242/P0000 Unit 98

Williamstown Historical Society newsletter No. 88, 1985, p. 5

Lemon, A; Morgan, M; Doyle, H; Buried by the Sea – History of Williamstown Cemetary, 1990, Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, Melbourne

Research: Ann Cassar & Graeme Reilly (ALHS 2019)