Migrants

In the aftermath of the Second World War the Australian Government made the decision to open up the nation to migration which was based on the notion of ‘populate or perish’. Between 1945 and 1965, two million immigrants arrived in Australia. Among the new immigrants were the first government-sanctioned non-British migrants. This enormous arrival of people transformed Australian society forever.

Arthur Calwell was appointed Australia’s first Minister for Immigration in July 1945. Addressing parliament a few weeks later, he stated ‘If Australians have learned one lesson from the Pacific war … it is surely that we cannot continue to hold our island continent for ourselves and our descendants unless we greatly increase our numbers … much development and settlement have yet to be undertaken. Our need to undertake it is urgent and imperative if we are to survive.’

Arthur Calwell’s call for immediate migration was significant but perhaps even more important were the final sentences of his speech: ‘The door to Australia will always be open within limits of our existing legislation to the people from the various dominions, United States of America and from European continental countries’.

For the very first time, the Australian government had acknowledged that it was willing to accept migrants from beyond the British Isles. The Australian government also introduced the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, launched by the government in 1945. The scheme offered British subjects subsidised passage to Australia and the promise of job opportunities and affordable housing once here. These new arrivals were known as ‘Ten Pound Poms’, named after the price of their fare.

Migrants from Britain and Europe contributed significantly to the tally of new Altona residents. In December 1947, the first boatload of 839 young Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians arrived in Melbourne. They were the vanguard of 182,000 displaced persons who came to Australia over the next four years. Almost one-third of them were Polish, but more than a dozen nationalities were represented.

A quarter of the total settled in Victoria, old army camps like Broadmeadows and Bonegilla were refilled with migrants, but more accommodation was desperately needed. In May 1949, the federal government: announced it would take over eighteen wool sheds at Braybrook and two hostels at the Williamstown racecourse, the wartime army camp. By importing Nissen and Quonset huts it was estimated that a further 2,000 or more migrants could be housed at the racecourse alone.

Nissen Hut, similar to ones used at the racecourse

The plan caused some outrage in Altona at the loss of a recreation area, although since the war, the course had been used only for horse training rather than racing. In December 1949, the new migrant camp took its first residents, among them Polish and Hungarian families. Then in April 1950, Kororoit Creek flooded and nearly one thousand people and their treasured baggage had to be evacuated to Broadmeadows for four days. It was noted that the old racecourse carpark across the creek had escaped flooding, and it was to this site that the hostel was transferred in 1951. It remained an unsightly collection of Nissen huts, lacking comfort and privacy, until brick units were built between 1966 and 1971.

The hostel name Wiltona reveals something of the attitude of old Australians to the newcomers. The poor, crowded conditions at the racecourse camp did little to ease the trauma of re-settlement, and by January 1951, there was concern at a succession of court cases arising from migrant drunkenness, traffic breaches, fighting and, more seriously, an attempted rape. To offset this poor image, the camp was visited by local newspaper people who reported on the talents, good citizenship, healthy outdoor sports and recreation arranged by residents. Polish, Italian and Dutch people were mentioned by name. Even so, the disorderly image stuck, at least with Williamstown councillors, who wanted their city name dissociated from the hostel. It was after all in Werribee territory, and Werribee, Paisley and Altona were all suggested before the composite name Wiltona was adopted.

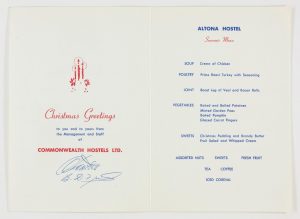

The migrant hostel on Kororoit Creek Road went by several names including Williamstown Migrant Hostel, Wiltona Migrant Hostel and Altona Migrant Hostel. In the late 1940s, migrants from war torn Europe began to arrive in Australia and quite a number were in Victoria. One of the migrant hostels was established on the east side of Kororoit Creek across from the Williamstown Racecourse and near the Commonwealth Oil Refinery in 1949. It hardly a hospital place with the nearly arrived migrants being housed primarily in clusters of ex-Army corrugated iron; half cylindrical sheds known as Nissen huts[1]. These had been there since wartime military occupation of the racecourse, supplemented by additional huts that were relocated from elsewhere.[2] The accommodation was community orientated, with the residents sharing outside toilets, but the ate together on long tables in a common kitchen area, and used communal laundry facilities. Each hut accommodated three families, who had about three rooms to each family. Cooking was forbidden within the individual accommodation, but this didn’t stop families from doing so.

An attempt to soften the harshness of the site was made by engaging the services of a prominent landscape designer, Mrs Emily Gibson[3], who specified several salt-tolerant species that were appropriate for the coastal site. In the early 1950s, the hostel was described as the only ‘mixed bag’ hostel in Victoria, that is the only one that, at that time, accommodated both English and non-English speaking residents.[4]

The Williamstown hostel site sided up against part of the COR/PRA (the refinery operated under the name of Petroleum Refineries Australia from 1960) site, that was next to the JT Gray Reserve and was bisected by a curving roadway that led towards a footbridge that crossed the Kororoit Creek, and lead to a recreation reserve[5] on the opposite side. The site was redeveloped in the late 1960s, when the hostel became one of several in Melbourne scheduled for major reconstruction works. Along with several other hostels, the Williamstown hostel was to be upgraded with clusters of new purpose-built brick accommodation blocks. This redevelopment took place over two stages: the first units were completed by early 1968, and the second by the end of that year.[6]

The units took the form of modestly scaled double-storey blocks, completed in brown-tinted concrete bricks, with gabled roofs clad in a matching cement tile. The blocks were arranged in irregular groups, creating a series of enclosed courtyards, and were linked by covered walkways. Designed by architect Reg Grouse, the new hostel buildings were subsequently nominated for a state architectural award in 1970.[7] Befitting its new image, the hostel was renamed, this time combining the names of both Williamstown and Altona and thereafter known as Wiltona Migrant Hostel.

The hostel was closed during the 1970s but was re-opened in 1978 to provide accommodation for the increased intake of refugees at that time.[8] This had abated by 1984, when the site was declared temporarily surplus to requirements, although the Commonwealth announced its intention to retain the hostel lest it be needed once again, in the future. The following year, however, the site was earmarked for disposal following an audit of the migrant hostel sites around Melbourne. The site was offered for sale in November 1986. An expression of interest to adapt the complex for emergency housing was abandoned, as the City of Williamstown councillors were opposed to continued residential use. The site was rezoned for industrial purposes and was subsequently redeveloped as a commercial and industrial estate known as the Williamstown Techno Park.

As it exists today, the former hostel complex can still be interpreted to some extent. Seven of the original clusters of units are still standing, although a few have been compromised by the infilling of their courtyards, and one has been almost entirely engulfed by subsequent additions and the old footbridge, across the Kororoit Creek, no longer survives.

View of units at former Wiltona Hostel, showing walkways and courtyard

Some migrants decided to stay within the area and their tastes were readily shared. In July 1955, a delicatessen and cake shop was opened by N Sarros and Sons in Pier Street. It was near the Strand theatre, which itself had recently installed the international film sensation Cinemascope. Delicacies in the new shop included the best of both Australian and Continental products, and it was proud to advertise ‘European languages spoken’. There were family connections with the cafe run by A Sarros for some years previously. On a wider scale too, Altona shared in Australia’s changing food tastes.

Some migrants decided to stay within the area and their tastes were readily shared. In July 1955, a delicatessen and cake shop was opened by N Sarros and Sons in Pier Street. It was near the Strand theatre, which itself had recently installed the international film sensation Cinemascope. Delicacies in the new shop included the best of both Australian and Continental products, and it was proud to advertise ‘European languages spoken’. There were family connections with the cafe run by A Sarros for some years previously. On a wider scale too, Altona shared in Australia’s changing food tastes.

Migrant sporting enthusiasms were more readily translated to Australia. By 1954, the Victorian Amateur Soccer Association had appointed an international coach from Britain to foster the sport. When he visited Williamstown, he marveled that in 1950 the district had struggled to raise a single team. One of its members was Altona’s Bob Stewart, then in his fifties. Four seasons later, there were two senior and two junior teams, and the Williamstown High School had joined the schools competition. All were said to be steadily moving up the competition ladder. local soccer was well established and able to accommodate the Altona teams which rose out of the influx of newcomers about 1960. Louis Noordenne was one of the local organisers.

British migrants may have been behind the formation of a yacht club at Altona at the end of 1953. Local cycle shop owner Fred Manning has been credited with the idea, although his enthusiasms by 1954 had transferred to founding a pedal club and then a pony club. In yachting it was the do-it-yourself era of small dinghies rather than the large, hence costly, yachts of earlier years. A few Altona members began building Cadets and then Hornets, both designed by Englishman Jack Holt and promoted by the magazine Yachting World.

At the 1961 census, 43 per cent of Altona residents were born outside Australia, compared with only 24 per cent of Melbourne residents as a whole. The Altona figure included 18.2 per cent born in the United Kingdom and Ireland, again significantly higher than the comparable metropolitan figure of 8.1 per cent. In addition, many of the 1.2 per cent born in Asian and African countries, even in Canada and America, may have been British citizens or colonials from the regions.

[1] A Nissen hut is a prefabricated steel structure originally for military use, especially as barracks, made from a half-cylindrical skin of corrugated iron. It was designed during the First World War by the Canadian American British engineer and inventor Major Peter Norman Nissen.

[2] Hobson’s Bay Heritage Study: Volume 1B, Thematic Environmental History, pp 6-7.

[3] Emily (Millie) Gibson nee Grassick (1887-1974) was a pioneer Australian trained horticulturist, the first female landscape architect and a campaigner for professional Australian landscape design training. She wrote prolifically for the Argus newspaper and worked on significant public landscapes.

[4] ‘Migrants will object’, Herald, 22 October 1952, p 3.

[5] This was the site of the old Williamstown Racecourse situated on the south of Kororoit Creek

[6] ‘Migrant blocks will house 500’, Sun, 9 February 1968.

[7] ‘Victorian Architectural Awards’, Architect (Victoria) No 8, March-April 1970.

[8] Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Government Operation. ‘Report on the delay in disposal of the Customs House, Wiltona Hostel and Rifle Range, Williamstown, Victoria’, unpublished report dated May 1987

Brooklyn Migrant Hostel

Opening in 1949, the migrant hostel at Brooklyn was located on the southeastern side of Millers Road and south of Francis Street, Brooklyn[1]. Within two years, the complex comprised thirteen former wool stores and eight Nissen huts.

The huts, which were divided into two, three and four-roomed flats, appeared palatial in comparison to the converted wool-stores, where 90% of the migrants were accommodated. Each of these buildings had been divided into about 100 small rooms, which were unheated, unlined and notoriously uncomfortable. In July 1951, a newspaper quoted one eyewitness, who stated that the wool-store rooms “have cold cement floors and, from inside, look little better than a barn”[2]. It was no coincidence that, only one month later, it was reported that a sum of almost £140,000 was to be spent on additional buildings.

In the early 1950s, the hostel facilities included a child-minding centre, a baby health centre, two first aid centres, a library and a general store. The migrant children were either taught at home or attended local schools. Later the majority of children attended the Brooklyn State School, which opened on an adjacent site in 1953.

Brooklyn hostel was once described in the newspapers as the ‘worst migrant hostel in Melbourne’ and the complex underwent little upgrading over the years. In June 1962, the kitchen and dining room block was destroyed by fire[3]. A temporary dining room was set up in the ‘hanger-like youth centre’, while an adjacent garage was remodelled as a makeshift kitchen. It was stated that a new kitchen and dining room would be erected as soon as possible.

In May 1967, the Brooklyn hostel was inspected by the then Minister of Labour, who subsequently ordered its closure on the grounds of substandard accommodation and the fact that its location was then in the centre of a developing industrial estate and was no longer deem a suitable site. By the following February, the last of the 300 remaining residents had been transferred to other hostels around Melbourne.

When the Westgate Freeway was laid out in the late 1970s, it ran along the southern boundary of the former hostel site in Brooklyn, and the land thus became desirable for new transport-related uses. A distribution centre was subsequently developed on the site. Now known as the Brooklyn Estate, this 22-acre site has been developed with several large steel-framed structures. None of the buildings associated with the migrant hostel are known to exist, and no signage or other interpretation has been installed to mark the site.

[1] Hobsons Bay Heritage Study: Volume 1B, Thematic Environmental History

[2] ‘Hostel poor but migrants want to stay’, Herald, 7 July 1951, p 3.

[3] ‘Fire or no fire: migrants eat after all-in effort’, Herald, 11 June 1962, p 3